Category: Uncategorized

Indigenous Education Week (Nov 1-5)

Ever since my whole school live Zoom presentation on September 30, the first annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, I have said that I wanted to continue the conversation.

I have not lived up to that as well as I wanted. I’m working on it.

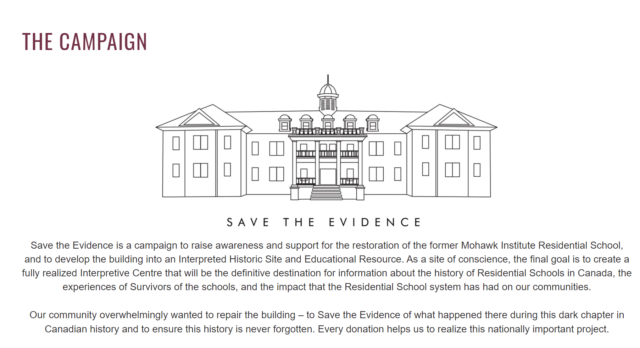

One thing I’d like to share is the “Save the Evidence” campaign from the Woodland Cultural Centre, home to the former Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School.

We know as historians how important primary source evidence is. That’s what the school building represents. People need to see it to appreciate its significance in the history of residential schools that Canadians are learning more about.

When I first drove up that driveway and saw that imposing colonial-style building, I felt uneasy. After learning more about the place known sadly known to students as the “mush hole”, I felt pretty sick. There is nothing child-friendly about it.

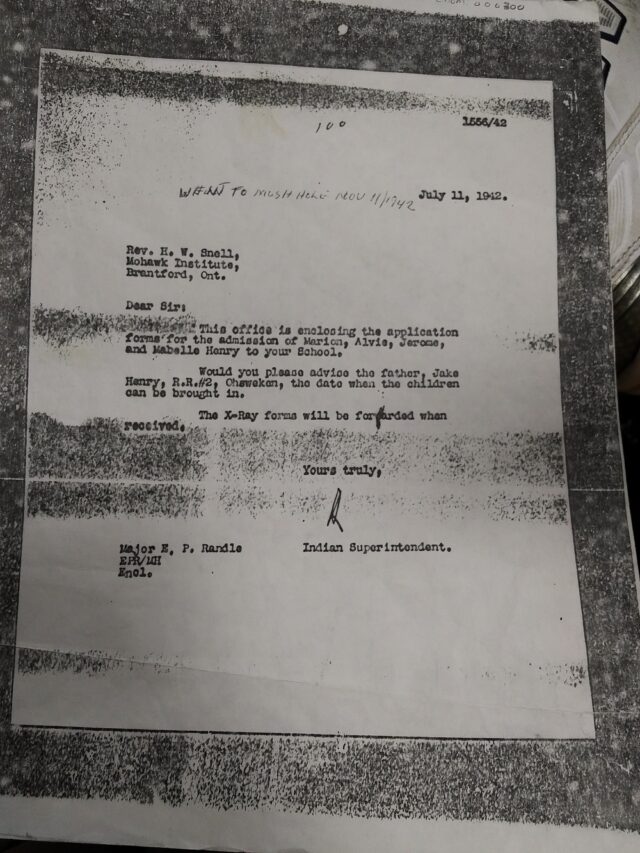

When our group visited Woodland Cultural Centre, we had the privilege of hearing survivor Geronimo Henry speak about his 11-year ordeal at the Mohawk Institute. He had a number of items with him – primary sources – including this letter that his mother sent the school to enroll him in 1942. Please note that Geronimo gave permission for me to take this photo.

We must always remember that history is about real people. Geronimo Henry, now in his 80s, speaks passionately about his experiences to educate the public about the impacts of residential schools.

Watch this short clip from Sept. 30 at the Mohawk Institute.

We must all keep learning and speaking out.

Dancing Cockatoo

There’s more to animal videos than cats, apparently. Val shared this dancing cockatoo. But more importantly, there are two cockatoos. One seems to be embarrassed by the other. Sounds like how Shadow feels about Richard.

Have a watch for a smile. And keep your eye on the bird on the left (even though it’s hard to stop watching the adorable dancing bird).

Studying For Exams

Try out some of these methods. They are scientifically proven to work.

Signs

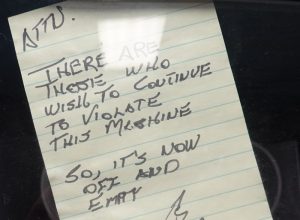

Who knows why I like signs so much? But clearly I do.

This note was attached to an empty vending machine at a laundromat in Dunnville, Ontario. I guess the owner had just had enough!

Ahead of the times: Meatless Days in this WWII poster found at the Transit Museum in Brooklyn, New York in 2014.

The original purpose for the now-famous Toronto sign was the opening ceremonies of the Pan Am Games in 2015, seen here.

Bells on Danforth

Val’s car came out for its second appearance, the first being Halloween, this Saturday for Bells on Danforth. It has been repainted in anticipation of the East York Canada Day Parade on Saturday.

- Notice it is now red and white.

- Notice the safety mirror.

- Fits right in.

- Why 53? I'm not sure.

- Welcoming riders at the park. There were probably about 500.

- A little "Greektown" fun.

Sugar

Sugar is a horse that I sometimes ride at Sunnybrook Stables. This post is not dedicated to her. It is about something that I associate with much more frequently than my once-a-week ride.

Sugar is a replacement swear-word that I sometimes remember to use when in the company of young, supposedly innocent ears. Again, it’s not the subject of this post, though I could benefit from a swear-cleanse.

Sugar is not the affectionate term I use to refer to my incredible husband. He’s ‘honey.’ As a vegan I am not supposed to consume honey, so it’s an odd choice. But it sticks, no pun intended.

Sugar is a word in the title of many books I’ve read on slavery and the slave trade. But it’s not my focus here.

No, what sugar really adds up to is my enemy.

To save myself, I tried to get off sugar last year, replacing my breakfast cereal (which was, in fact, rather low in sugar comparatively at 2 grams per serving) with plain oatmeal (the really fibrous kind) that I’d eat with half a banana. That didn’t last more than a few months.

Following that failed attempt I found myself stuck on an even more sugary cereal, oatmeal squares, at 7 grams of sugar per serving. It is recommended that we don’t eat anything over 5 grams of sugar per serving.

Apparently I did not conduct my sugar reduction in the right way. I made myself crave it even more.

This is all very weird coming from a vegan who does not eat dessert. Well, I do admit to a liking for fake ice cream – that’s soy and coconut to you unaccustomed non-vegans. I am able to contain that craving by only having it on special occasions. Note to my mom: stop buying it, please. Thursdays aren’t that special.

So, how is a sugar demon to be slayed?

After this current box of oatmeal squares is finished, I swear I’ll stop.

Tune in later to see if sugar wins.

Post-sugar script: There’s an app for it: See this Guardian article.

Ottawa

I recently had the pleasure of a short visit to Ottawa. Val joined me after the OHASSTA conference. Preparations are definitely on for Canada 150 – the 150th birthday of our country, in case you didn’t know. There’s construction everywhere – it feels like Toronto.

The weather was absolutely perfect for fall and there were still some red, orange and yellow leaves. The scenery around Parliament Hill is worth the trip.

We had an interesting visit to the War Museum. The special exhibit Deadly Skies – Air War, 1914 – 1918 was really informative. I learned so much about all kinds of uses of air technology in the war: balloons, zeppelins, airplanes for battle, airplanes for observation. I looked at detailed reconnaissance maps made from aerial photos. I saw how even the Red Cross got into the spirit of battle by selling little pieces of destroyed German zeppelins to raise funds. Overall, though I found it fascinating, I was saddened by the overwhelming realization of how far war pushes technology. When the war started pilots were dropping bombs out of their planes by hand. By war’s end, there were multiple types of bombs and they were massive.

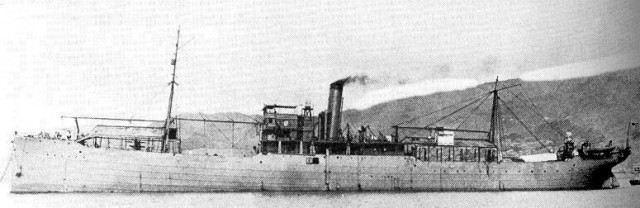

For my last year’s grade 12 students who inquired into “was World War I really a world war?”, I’d like to report that the air war actually began in the Far East when Japan bombed the warships at port in the German territory of Tsingtao in China in 1914.

Wakamiya, Japanese ship carrying airplanes that attacked Tsingtao. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Tsingtao

A word about the architecture of the War Museum: it is meant to throw you off somewhat, but I felt it to the maximum. I had to leave after spending too much time in its bunker-like lower level where all the tanks, trucks, and artillery pieces are kept. While we were there they were setting up for a Habitat for Humanity gala. Quite the incongruous setting. They called it ‘Steel Toes and Stilettos.” Well, I’m sure they raised a lot of money for a good cause.

Auction from Habitat’s 2015 gala.

Hallway leading downwards to lower hall in War Museum.

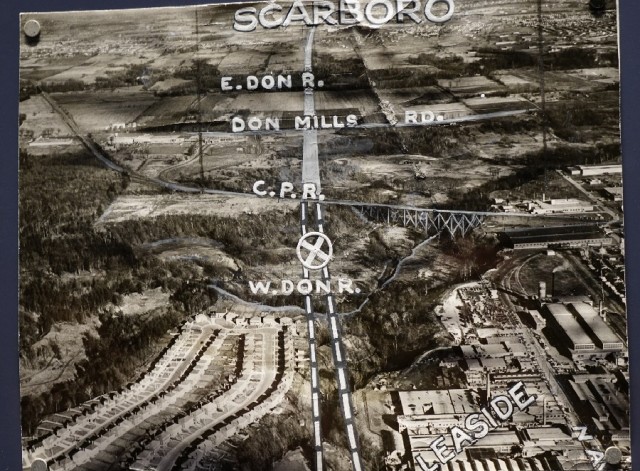

Having spent a lot of time photographing the National Gallery from the outside on Saturday, we made it in on Sunday. It’s a beautiful building, but once again, I found that I reacted negatively to all the concrete. On the plus side, we enjoyed the Toronto-centric exhibit Cutline: The Photography Archives of the Globe and Mail (that national newspaper). This photo shows the proposed extension of Eglinton Avenue east of Brentcliffe Road. My mom should appreciate this – her new condo complex is located approximately where the CPR line meets the extension. Of course this photo is pre-Inn on the Park (opened 1963) as well as pre-condo (2004). The two streets of houses north of the extension appear to be Thursfield Crescent and Rykert Crescent. The western portion of the extension was actually built in 1956, according to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eglinton_Avenue.

Val keeps saying he’d like to return to Ottawa in the summer some day. I don’t think next July 1st, 2017 will be a good time – it’s apparently booked up already!

A Surprising Book for Ms G

Wade Davis, Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest. Knopf Canada, 2011.

I don’t like the thought of mountain climbing; it makes my palms sweat. I do like Wade Davis. That would explain why I picked up a hard cover edition of this 578-page behemoth a few years ago at my local Book City. Thinking back, I was probably also very attracted to the “Great War” part of the title having been on a World War One kick.

Despite the subject matter’s initial lack of appeal, it grew on me. Remembering back to The Wayfinders (which I sometimes use in HSB class – Challenge and Change in Society – to introduce the discipline of anthropology) I recall Davis’ beautiful way with words. Sentence construction, or rather, poor sentence construction, can be a real stumbling block for me in getting through a book. Not so this one. Davis is sleek and clever without being pretentious. Even when the subject matter is pretentious it doesn’t seem so, such as the detailed descriptions of the snooty English public school educations of the lead characters. Or the champagne that they ship across the world to be carried up Mount Everest by Sherpas.

The Great War is part of the subtitle but really deserves top billing. The war in which most of the climbers of the first three British expeditions in the 1920s fought is the glue that binds them all and sets their characters. In that sense it’s the context of the story. However, it builds to so much more. Getting to the summit becomes a battle in itself, three times: classic “man versus nature” stuff (weren’t we all taught that it’s one of the universal themes of literature back in grade seven?). It turns out that it does make for a gripping theme. At first the mountain-climbing-phobic reader finds little interest in the actual expedition. Drawn in bit by bit, or rather foot by foot or camp by camp, the loyal reader is nearly cheering for Mallory to reach the summit even though the tragic end is already known. Biting wind, blinding sun on snow, inept supply chains, broken oxygen apparatus – they cannot defeat the experience and sheer will of Mallory.

In the end it’s not about conquest of nature. It’s about respecting the power of the mountain. Without shoving that theme in the reader’s face Davis makes the point.

Davis also uses an anthropologist’s eye combined with a historian’s brain to reveal the ways the British perceived the Tibetans and their seemingly strange rituals. Being the master of all trades, Davis additionally highlights the photographic firsts that occurred on the mountain and the lengths that photographers went to to take and develop their breathtaking shots.

Since I read The Wayfinders I have said that Wade Davis has the perfect job: National Geographic writer and photographer. As a history teacher, sometimes anthropology teacher, and very amateur photographer, I am jealous.

February 13 Presentations

Hello. Thanks for attending. Here are my presentations.

SWSH_Feb_2015_Assessing_Historical_Thinking

Here is the Idle No More lesson. Thanks to my co-writer, Rick Chang, also from York Mills. We’d love to hear your feedback.

Aboriginal_Canadians_Historical_Perspectives