Ever since my whole school live Zoom presentation on September 30, the first annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, I have said that I wanted to continue the conversation.

I have not lived up to that as well as I wanted. I’m working on it.

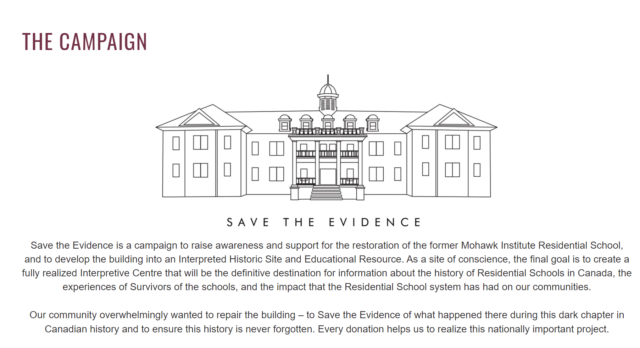

One thing I’d like to share is the “Save the Evidence” campaign from the Woodland Cultural Centre, home to the former Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School.

We know as historians how important primary source evidence is. That’s what the school building represents. People need to see it to appreciate its significance in the history of residential schools that Canadians are learning more about.

When I first drove up that driveway and saw that imposing colonial-style building, I felt uneasy. After learning more about the place known sadly known to students as the “mush hole”, I felt pretty sick. There is nothing child-friendly about it.

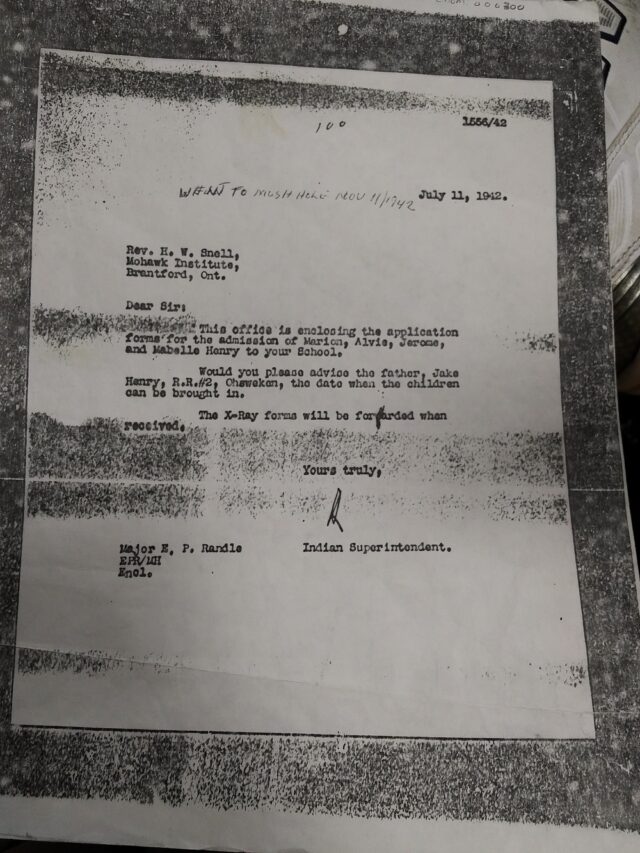

When our group visited Woodland Cultural Centre, we had the privilege of hearing survivor Geronimo Henry speak about his 11-year ordeal at the Mohawk Institute. He had a number of items with him – primary sources – including this letter that his mother sent the school to enroll him in 1942. Please note that Geronimo gave permission for me to take this photo.

We must always remember that history is about real people. Geronimo Henry, now in his 80s, speaks passionately about his experiences to educate the public about the impacts of residential schools.

Watch this short clip from Sept. 30 at the Mohawk Institute.

We must all keep learning and speaking out.