2021 Reading

I did not read nearly enough books this year. Blame it on the pandemic, I conveniently and shamefully say.

I started and got 300 pages into Barack Obama’s A Promised Land, really liking the personal and family bits. But I found myself politically tired as I read the sections on passing bills in Congress. By the time Afghanistan rolled around I could not stomach it anymore. I really admire Obama’s non-cynical nature and his careful examinations of his decisions. However, reading about damned if you do and damned if you don’t discussions on Afghanistan just tested my patience too much and I abandoned the book, hoping to return one day.

This one I got through pretty quickly. As usual I picked it up at my local Book City on one of the remains table. Liking social histories, I thought it would offer a good perspective on those who don’t always make it to the historical headlines, domestic servants. Yes, I’m a fan of Downtown Abbey and I used this book as a measuring stick to gage Julian Fellows’ historical accuracy! That aside, the book was fast moving, filled (nay – jammed) with incredible quotes. The only problem was I probably ended up learning more about the wealthy employers than the servants themselves. That is partially owing to the nature of the sources.

I have no problem plainly saying that every Canadian should read this book. Though I considered myself relatively educated about the Indian Act prior to reading this short but devastating book, I realize that was just dispersed knowledge. Here Bob Joseph puts it all together, with historical context, quotes and commentary, in a way that is incredibly readable and relevant. There is just no way to understand Canada’s history without a full picture of the intents and damages of the Indian Act.

I’m not ashamed to admit I read Romeo and Juliet for the first time in modern English “translation.” Though I am of course familiar with the story through movies and the ballet (to which I took my mom some years ago), I had not actually read the play (it was Twelfth Night for grade 9s at St. Andrew’s Junior High School back in the 1980s). I started out reading the original play but I found it very difficult to navigate those little footnoted comments on the bottom of the page. My aging brain just could not handle going back and forth – it just broke the momentum of the narrative. So I picked up a few copies of the No Fear version, intending to read it with one of my credit recovery students. That didn’t happen. Nevertheless, I found it a fast-moving, relatable story. It provoked some uncomfortable thoughts about young love and its not so reliable passions.

I have now nearly finished this new book from Margaret MacMillan. Even when I am tired on my morning subway and bus rides, if I am sitting, I pull it out. It’s quite an addictive, easy read. Most of the examples are western, many pulled from the World War One era. Obviously I feel most comfortable with this book when it’s on familiar terrain (both the author’s and mine). She challenges me as a history teacher who likes to ignore war as too messy a subject, reminding me that so much comes of war. True. True. As much as I have enjoyed it, I would like to see the author stop using “the great” as a descriptor for all kinds of historical figures. It drives me mad!!!

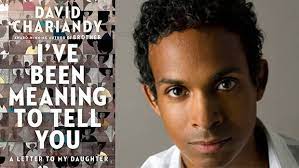

The few other books I read this year have already been reviewed on this blog: David Chariandy’s I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You, Melissa Gould’s Widowish, and Dava Sobel’s The Glass Universe.

I resolve to read more this year, starting with Malcolm Gladwell’s Talking to Strangers which I just received as a gift from the kind and generous Barry Pietersen.

Special magazine mentions:

When I’m on the streetcar heading down to riding at the Horse Palace, I often bring a copy of The Walrus or Scientific American. Here are some standout articles from this year.

“Journey into the Americas” by Jennifer Raff, Scientific American, May 2021 – about when and where the early people of North America came from (I am fascinated by this topic as a world history teacher)

“Deadly Kingdom” by Maryn McKenna, Scientific American, June 2021 – about the rise of fungal diseases (surprises lurking)

“Why Animals Play” by Caitlin O’Connell, Scientific American, August 2021 – who wouldn’t want to read an article accompanied by cute animal photos

“Lifting the Venus Curse” by Robin George Andrews, Scientific American, September 2021 – the case for new missions to study one of Earth’s closest neighbours

“Women at Risk” by Melinda Wenner Moyer, Scientific American, September 2021 – part of a special report on autoimmune diseases, this article really shows the double burden of the female body – incredibly interesting potential reasons why suffer disproportionately from autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

“Northern Inroads” by Gloria Dickie, The Walrus, Jan./Feb. 2021 – surprising ways China is making its way into Canada’s north

“How Immigration Really Works” by Kelly Toughill, The Walrus, May 2021 – we always think of federal jurisdiction when it comes to immigration but these days so much more is locally driven

“Justice on Trial” by Eva Holland, The Walrus, June 2021 – Canada’s legal system through the eyes of Indigenous Canadians

“Students for Sale” by Nicholas Hune-Brown, The Walrus, Sept./Oct. 20`21 – an indictment of the international student racket run by Canadian colleges and universities.

“The Campus Mental Heath Crisis” by Simon Lewsen, The Walrus, November 2021 – important reading for a high school teacher – the need to know what happens to mental health after high school is pressing

“The RCMP Revisited” by Jane Gerster, The Walrus, November 2021 – fascinating history of the national police force and its origins in the policing of reserves