I wanted something a bit lighter and quicker for my spring subway reading so I turned to YA fiction to keep up with possibilities for credit recovery (NOT next year). Earlier in the year I had read the entire Hunger Games series for credit recovery, though it turned out the neither student got past chapter 10. No worries, I enjoyed all three books – far more than the movies (which I also watched simultaneously on Netflix). I also read Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes, more of a children’s book, as I was using it for two students in credit recovery on Mr. Bryant’s excellent recommendation. It is an excellent, easy reading book with a powerful story about a 12-year old Black boy shot in Chicago. He tells the story from the perspectives both of being dead and alive. He is taught to be a ghost boy by the ghost of Emmett Till. I wish my students had cared more about the moving nature of the book. Though it only took about two days to read, I cried a bunch of times. They got through it (which is meaningful) without much connection.

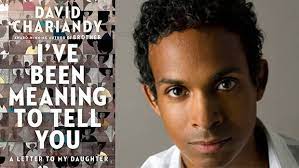

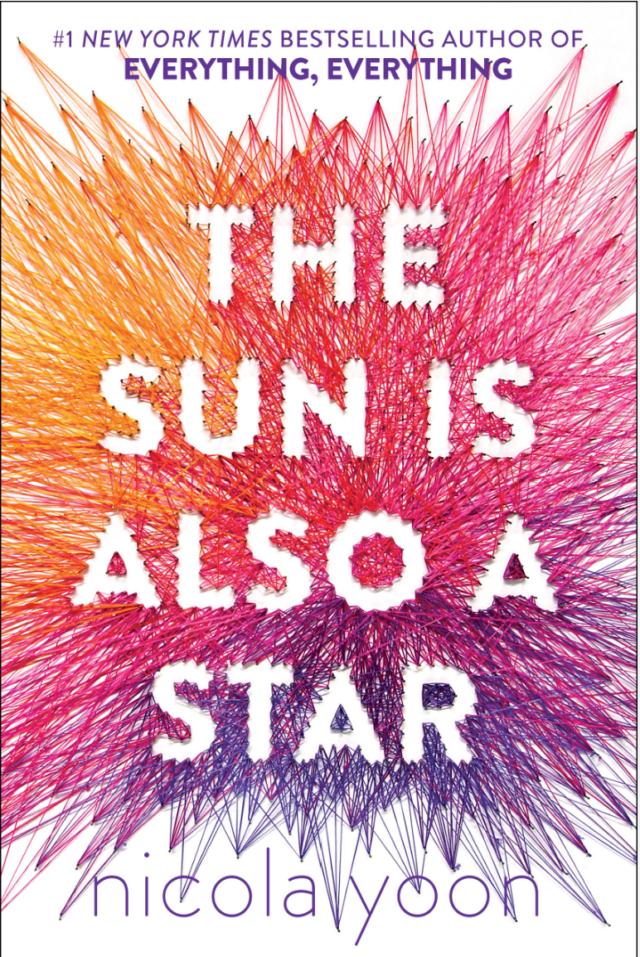

The Sun Is Also a Star, by Nicola Yoon; A Very Large Expanse of Sea by Tahereh Mafi

I very much enjoyed the dual perspectives (two characters relate an event in different ways) in The Sun Is Also a Star. The whole time I was reading the book (about 3 days) I was thinking about how I could use these perspectives with students in English credit recovery even if they don’t read the whole book. I heard it was made into a movie as well. However, after watching the trailer I buried what I had seen. The book IS always better.

I had started A Very Large Expanse of Sea about a year ago. I got about a chapter in and decided I didn’t like it because the main character swore too much; this felt too forced. So I put it away. I decided to give it another go. This time I loved it. I guess I had to be in the right headspace to read young adult fiction. The narrator has a very strong voice and is an interesting character, not an easy-going character. I like her sharp tone. I will admit the book brought back a lot of high school memories, some pretty painful in retrospect.

How the Word is Passed by Clint Smith

This is a highly engaging, relevant, hard-hitting book. I had heard about it from the New York Times best seller list last year. So I bought it in February as part of a collection of books to be given as gifts from THHSSSC to people who came to the subject council session at the SWSH PD conference at York Mills. No one wanted it so I kept if for myself but held off taking it home feeling kind of guilty. It was worth the wait.

The subject matter is exactly the hard stuff I love reading about: the history of slavery in the US. But the framework is so clever. Clint Smith travelled to sites – museums, cemeteries, plantations, Angola state prison in Louisiana, to name a few – that have deep connections with slavery; some of them are honest about that history, some of them are not. He went on tours and spoke to fellow tour members and tour leaders. He spoke to experts and researched on his own as well. The result is a meshing of excellent history with beautifully written prose. It is both a timely book given the polarization in the US, and a timeless book given its deep, pensive approach to a very difficult conundrum: how Americans consider (or don’t) slavery in their view of their country’s history.

There were times while reading this book on the subway that I had to stop, put it down, and shake my head. During the author’s tour of the Louisiana State Penitentiary known as Angola, I learned that the US – to this day – has a number of states that do not require unanimous jury verdicts in trials. I was floored but not shocked when I learned the reason was to sideline Black jurors. Similarly, when Smith relayed the average length of sentence in the prison is 87 years I just had to stop reading for a while. All of the chapters are very indicting but the Angola one really shocked me. I don’t know why; it is obvious that mass incarceration is a direct descendant of enslavement.

I’d like to divert to a film review here. About a month before I started reading How the Word Is Passed, I saw a meaningful documentary on Netflix. In retrospect, it pairs very effectively with this book. Descendant shares with the book the perspective that history matters, memories matter. It is the story of a community of people in Alabama who are the direct descendants of the last enslaved people brought to America from Africa over 50 years AFTER the slave trade was made illegal. The premise for the movie is that the there is a new search for the ship, the Clotilda, that was scuttled by the owners in 1860 after it dropped off 110 people in Mobile. The community, Africatown, part of Mobile, Alabama, is coming to grips with what it means, how it should be commemorated, and, for some, how it can bring tourism to the town. It turns out the story isn’t just about the ship and the people who began their forced journey to enslavement on it. The town, very similar to Africville in Nova Scotia, has been a dumping ground for heavy industry for decades as Mobile encroached. There is one moment in the film where a person is walking in a leafy, green section of the town. The camera suddenly pans up to an overhead drone shot and huge smoke stacks are revealed. The town is surrounded by pollution and has high cancer rates (reminds me of Fort McMurray in northern Alberta). One of the last scenes in the film is of a young activist who is taken on a tour of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC led by one of the curators who has been to Africatown to work with the community in the aftermath of the discovery of Clotilda. She is awakened to the power of history. I was ALL in.

Back to the book, I learned a lot even though I consider myself knowledgeable about slavery in the US. Starting with Thomas Jefferson’s plantation in Virginia, Monticello, Smith reports facts about his selling and moving of enslaved people as a means of paying off his personal debts. Some white women on the tour were shocked. Their education on slavery had been limited, part of Smith’s point. Then he goes to Whitney Plantation in Louisiana to learn about a plantation with its enslaved people centered in telling its story. Then to Angola where the prison obfuscates about its history as a plantation and its smooth transition post-slavery to using essentially unpaid the labour of the inmates. Following the prison tour, Smith goes to Galveston to experience and investigate Juneteenth, the celebration/commemoration of Texas’ freeing of the enslaved people. Here he explores the intersection of facts and memory. Next, Smith visits a Civil War cemetery where folks are commemorating the Lost Cause view of the Civil War pretty much completely in opposition to what the war was really about. Interestingly, he also travels to New York City and takes a tour of several areas of the city with Black pasts that aren’t very well known, including to a section of Central Park which was once a Black community. In the penultimate chapter Smith travels to Senegal to look at the telling of the story of slavery from the African perspective and confronts, once again, the complicated relationship between historical fact and historical memory, this time in relation to the infamous House of Slaves which cruelly sent off thousands of enslaved people to their fate in the new world. I found it quite poignant that Smith chose to end his book by exploring the history of his own grandparents by having them share their experiences with racism, Jim Crow, education, and finally, memory.

This book reaffirms for me how much I am grateful to have a career in which I get to instill the importance of history to current day life. Without it, we flail and move backwards.

The 99% Invisible City by Kurt Kholstedt and Roman Mars.

Val bought this book. It’s by the guy who hosts the 99% Invisible podcast, apparently. I haven’t listened to it but I enjoyed the book as its focus is on urban architecture and design (one of Val’s favourite topics, and thus mine, too). It has very short chapters (about 2 pages) that reveal little known facts about cities, ranging from the design of emergency vehicles to the design of lamp posts. Perhaps the podcast is a little bit more in depth. I enjoyed it (note – I am 99% done reading it). But it was too heavy to read on the subway. It’s more for my night table.

What If? 2 by Randall Munroe

This book is also too heavy to read on the subway, but I took it for a few weeks as I needed some lighter fare. The best way to describe this book is: smart, funny, really useless stuff based on science. In other words, Donald Trump wouldn’t read it. Well, I don’t know if he can read. It’s not exactly my thing – I will probably never finish this book. But when I need a ‘smart’ laugh, I will pick it up and learn something that I will never be able to use in real life since I am not planning to create a tower from here to the moon or to know if a plane can be launched by catapult.