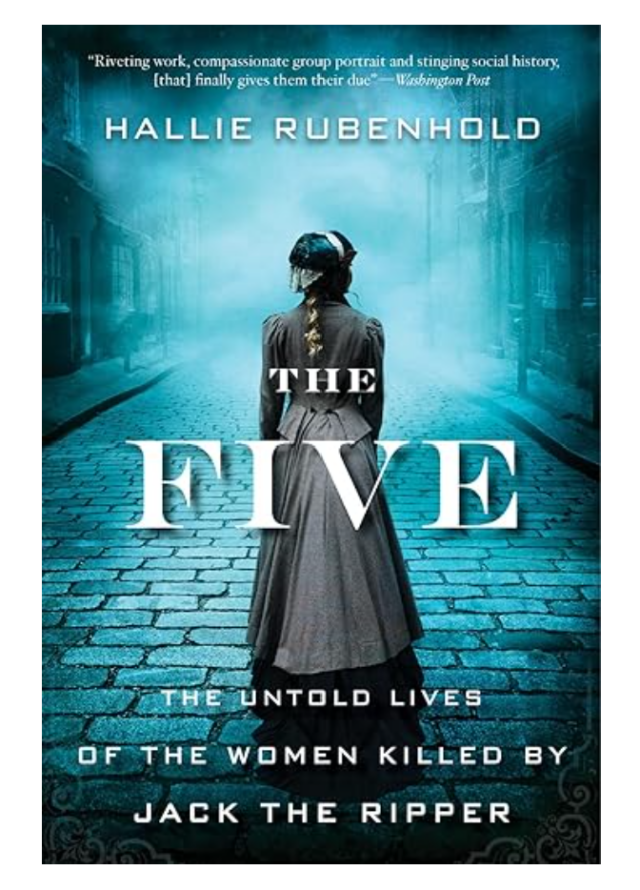

The Five – An Astonishing And Heart-Wrenching Book

Hallie Rubenhold possesses the best of the writer’s and historian’s skills. She gets it – and is able to communicate such in a beautiful and frank way – that history isn’t solely about the past: it’s about bettering the world of today by making the reader see complexity instead of simplicity. Late Victorian British social history carries so many parallels with today, especially the gap between rich and poor and the moralizing that goes on when one group looks at the other.

Imagine this: a book about the victims of Jack the Ripper with not a single detail about their deaths. Rubenhold has investigated every detail that can be found (or triangulated) about the lives of Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elisabeth Stride, Catherine “Kate” Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly.

The other day while waiting for the bus outside Dufferin Station, I saw a woman sitting on the ground, obviously not in the best of health. She had many bags, was coughing, and smoking something so horribly foul smelling. It’s easy to turn a blind (or crude) eye these days to people on the streets. But I caught myself: what is the difference between her and the five women? On that same day, on the bus, a man called a woman a “f-ing b_ _ _ _.” A woman chastised him, even challenging him to a fight. I felt the spirit of the women on that bus, not because they’d be quick to a fight but because they had to stand up for themselves every single day!

Rubenhold goes to great lengths to paint many-layered pictures of the five women’s lives. The common factor was struggle, both as women and as members of the working class. She is careful to say what is not known for sure (documents being lost, not all things being able to trace). But she also uses the conditional tense throughout to infer the potential feelings and conflicts of struggling women of that time and place. This is particularly true for their relationships with the men in their lives.

Rubenhold’s subjects are women who didn’t always have a place to stay at night. Gerunds abound: tramping, charring, prostituting themselves (in only one case for sure). Signing themselves in and out of work houses. Having children die in their arms. Coming from situations where multiple siblings died. Losing parents to disease at a young age. The tragedies went on and on.

There’s a lot of talk, not surprisingly but also sensitively, of alcohol and alcoholism. In the passage below discussing the fifth victim, Mary Jane Kelly, Rubenhold shows her gift of positing what might have run through the woman’s mind:

However, drink also offered a convenient escape from a miserable existence. It dulled the fear of unwanted pregnancy and disease, a very real possibility in every penetrative encounter. It obliterated and it quieted, even for a short time, feelings of self-loathing, guilt, and pain, and traumatic memories of violence.

Earlier in the book, Rubenhold tells the complicated story of Kate Eddowes, liver of an almost nomadic life, for a time, as a seller of chapter books and ballads. Travelling Britain with her ‘husband’ Thomas Conway, they often attended hangings in search of crowds to buy their tales. In one instance, the person being hung was a relative of Kate’s. Kate, being literate, would certainly have had a hand (if not sole authorship) in the writing though Thomas seemed to see himself as the author. Rubenhold quotes from the ballad which shows sensitivity to the plight of the condemned relative. Once again Rubenhold sees the humanity in Kate even at the most gruesome time:

Satan, Thou Demon strong,

Why didst thou on me bind?

O why did I allow thy chains

To enwrap my feeble mind?

Before my eyes she did appear

All others to excel

And it was through jealousy,

I poor Harriet Segar killed.

May my end a warning be

Unto all mankind,

Think on my unhappy fate

And bear me in your mind.

Whether you be rich or poor

Your friends and sweethearts love,

And God will crown your fleeting days,

With blessings from above.

At the end of the book, Rubenhold includes a list of the items found on four of the women. I find this a particularly effective, if chilling, way to end the book. Mostly the lists are filled with items of clothing, for layers were probably a survival tactic. Kate’s list is the most interesting to me. In addition to bonnet, jacket, and multiple skirts she had tin boxes of tea and sugar, soap, knife, teaspoon, cigarette case, pawn tickets, a partial pair of glasses. Finally, “twelve pieces white rag (some slightly bloodstained (menstrual rags).”

Hallie Rubenhold has brought hidden lives back into the light.