Cold can be nice down by the lake. The Beach. Lake Ontario, January 2, 2026.

Toronto Is Still Good…Mostly

I forced myself to leave the house on Saturdays in November and December instead of just sitting home and working the ENTIRE weekend.

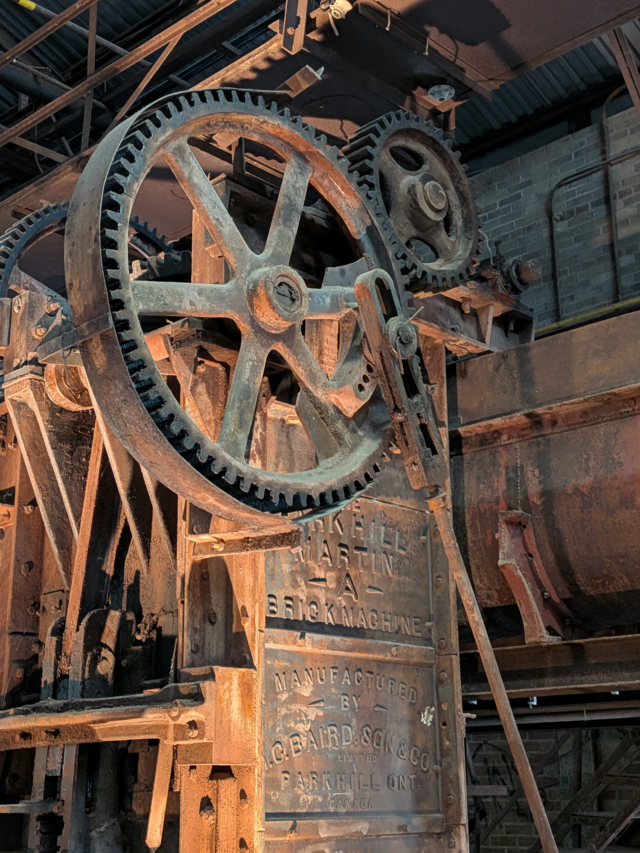

Brickworks Brick Machine

Don River restored at Biidaasige Park

FIFA Renovation at BMO Field (hopefully not too late)

Giraffe at the Brickworks

Horse Palace at Exhibition Place

Horse Palace at Exhibition Place

Stall architecture at the Horse Palace

The owl at Biidaasige Park

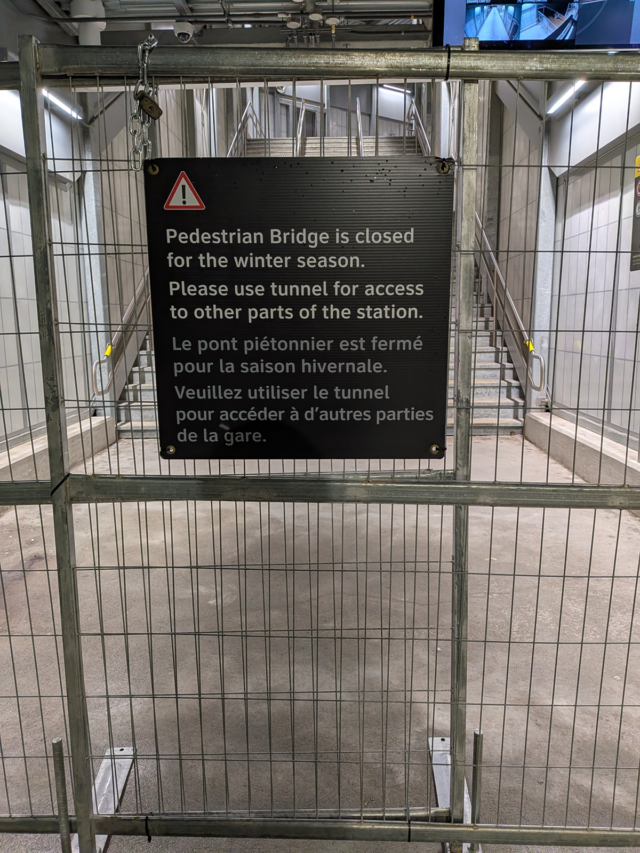

Bridge closed over the Go tracks at Exhibition

Raccoon slide at Biidaasige Park

The new North Market building

St. Lawrence Market

Sunset over Riverdale Park East

There’s a lake – even during a rainstorm

Fall Book Review

Who knew a book about urban evolution could be so amusing? I would have said not me, but I must have had an inkling because I picked this book off the remainders table at my local Book City. Likely it was my interest in Darwin that captured me. I’m a sucker for naturalists’ writing, too, as evinced by my steady stream of recently read books on birds and octopuses.

Menno Schilthuizen’s easy to understand and humourous 2018 book, Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution, provides a great overview of the numerous ways evolution is occurring in cities around the world. As usual for a book chosen by me, there are plenty of bird examples; house crows in Singapore and the Netherlands, parakeets in Paris and London, even the so-called finches in the Galapagos Islands that are continuing to evolve because of the influx of tourists: note, they are apparently not even finches. There are also the unfortunately named turdus species: blackbirds. Let alone the milk-bottle opening tits in the UK that have found ways to get at the cream at the top of delivered milk bottles, and the carrion crows in Japan that open walnuts by going to busy intersections where cars run them over. Fancy tool use!

Animals are not just ingenious because of their brains. Their brains are ingenious because certain genetic traits have been selected by nature/evolution. There are seemingly simple examples related to the colours of moths in industrialized cities (the darker the better to camouflage them in sooty settings) and complex examples such as the moths that are attracted to lights and their city relatives that may be less attracted to lights because of their prevalence. Natural selection (and all its various sub-type – take grade 12 bio if you want details!) is a powerful force.

Perhaps the most surprising stories in the book deal with seemingly innocuous situations: city plants that invade the cracks in sidewalks, the fungi and microbes found in soil (and bathrooms), spiders residing on bridges. The scientists, both professional and citizen-oriented are the ones saving the day with their reason, observation and data-driven respect for knowledge and reason. In these days of anti-science, we must take all opportunities to recognize and reward actual thinking.

As the world becomes more and more urbanized, while the human population continues to grow with little regard for sustainability, it will be our cities that will serve as a potential haven for wildlife in all its forms.

East End Outing

Riverdale Farm Fall Festival, Cabbagetown Art and Craft Show, and Cabbagetown Festival on a lovely Saturday afternoon.

Clouds over Parliament Street

Cow at Riverdale Farm

Really, farm-raised beer? Nearby there was a licensed daycare called Buds and Blossoms. Are they serious? There was a lineup there.

So many beautiful gardens in Cabbagetown

Greyhound tush – his mom fixed his PJs right after I took this photo

Horse – probably pony – at Riverdale Farm with his City of Toronto high visibility leg wraps

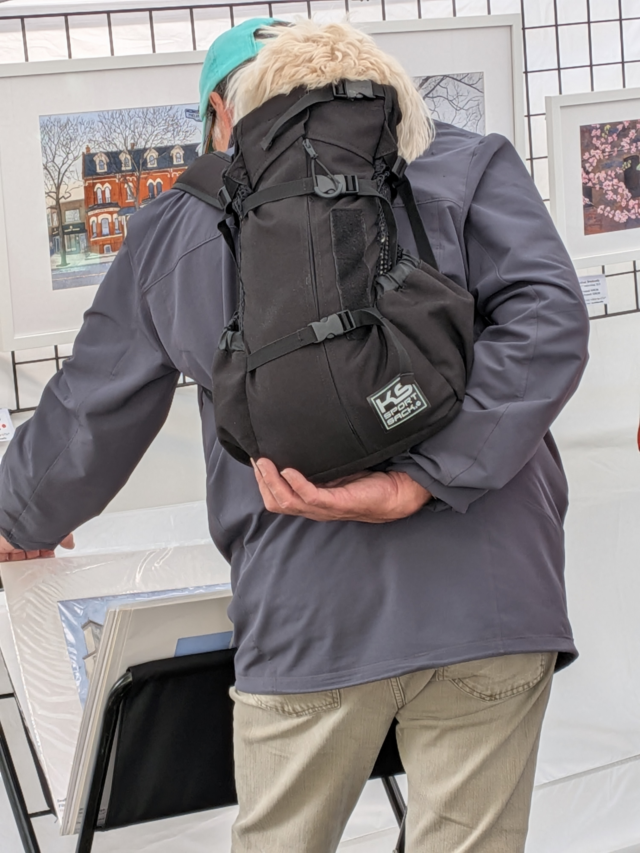

A man checking out the art with his dog in a backpack

Pickleball court in Cabbagetown – who knew?

Riverdale Farm ponds

An Onion and an Octopus

This summer I admittedly wanted light reading. With the world in such critical condition and the summer weather so extreme, I just needed a break from my usual heavy history or world events books.

So, I started out with Mark Kurlansky’s The Core of an Onion. A lot of thought was not put into that choice; the author is known to me – he’s a good one having written two of my favourites: Salt and Paper – and I have a “meh” relationship with the subject. It was on the sale table at Book City (as are most of my book choices). In other words, there wasn’t much else that was available at the time, having just finished the very intense Fire Weather, so I picked it up. It was cute; I learned a few things about onions. The recipes at the end weren’t vegan…. That’s really all there is to say.

Then, looking for something else, a person at the bookstore recommended The Soul of an Octopus to me when I was checking out options in the nature section. Lucky me!

Written by Sy Montgomery and published in 2015, this is probably the best known of her MANY books. She writes about nature, obviously, but she does it with a very personal touch. Much like Jennifer Ackerman whose bird books I read on my year off, Sy writes in what I would call a “warming” style. I felt endorphins calming me while I was reading the book on the subway, bus, or streetcar. This book literally made me cry on the subway home during the week before school started this August (2025). No one rushed to help me, just so you know.

Sy befriends humans (employees and fellow volunteers) and octopuses alike at the New England Aquarium where she falls in love with octopuses almost from the start and interacts with them, frequently – literally putting her hands in the water to touch their tentacles, or, rather for them to touch her hands. She is inspired to learn how to scuba dive in order to see octopuses in their natural habitat. And sadly, she experiences the deaths of young Kali and senior Octavia. Probably one of the lasting things I will always remember from this book is the information about the short life span of octopuses, living only one to five years. Nature works in surprising ways; elephants, also very clever animals, live for maybe 60 to 70 years.

Like other readers who have reviewed it, I don’t think this is a perfect book. It’s rather simplistic, especially in comparison to fellow nature writer Jennifer Ackerman’s meticulously researched work, in my opinion. To clarify, I have not read any scientific articles or books about octopuses. It’s a bit anthropomorphic, though humans are generally so in our impressions of the animals closest to us. And, it’s about captive animals rather than wild ones, for the most part. While I admit that I visited many zoos and aquariums when I was young, I haven’t been to an aquarium since 2006 when we went to the fantastic Monterey Bay Aquarium, and I haven’t been to a zoo also since we went to the famous San Diego Zoo on the same trip. As a person (and vegan) who loves animals and nature in general, I don’t love visiting zoos to see animals in unfortunate, cramped captive situations. On the other hand, I have two cats and I ride horses. Am I hypocritical? Probably. Just fyi, I’ve never eaten octopus.

I don’t mind too much that the author didn’t approach the consciousness topic very deeply. I don’t need to be persuaded that animals have consciousness, intelligence, emotions, etc. Philosophy is not something I am interested in. I just live and think and don’t really have a structural methodology to my thinking. So be it.

Overall, on the one hand I loved the octopuses and the cast of human characters who gather round the tanks (and the pickle barrel where Kali lived). And I appreciate Sy’s kindness – she emailed me back a lovely personal note when I emailed her as I almost always do when I finish a book. Though, on the other hand, I didn’t find it to be nuclear physics. That’s okay. I’ll probably pick up another one or two of Sy’s books, and I will try to use some of the writing to lure my students into reading anything other than texts.

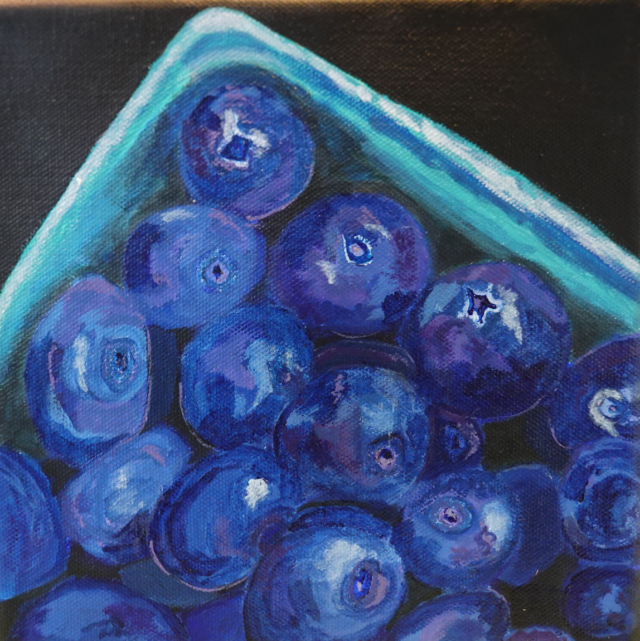

Summer Art

I’d like to give credit to the original artists.

While it may seem vain to post all these paintings, it really just helps me become better at this skill. I do have a few original pieces but they are not ready for showing quite yet. Happy painting.