2024-25 TTC Best Books

Here are some of my favourite reads this year from my commutes to and from school, not including my usual magazines: Scientific American, Canadian Geographic, The Walrus, and Spacing.

The TTC wasn’t perfect this year (I’m talking about you -the Dufferin bus on Thursdays!). But commuting by public transportation allows me time to read! In the age of AI, there is no greater good.

Favourites!

Also

I tried to get through this one but just found it too dense – and heavy – for TTC reading. I didn’t expect such a scientific approach to history – too much for a.m.

Last but NOT LEAST

Stars on Ice 2025

Fun show. Great seats – on the floor right in the middle of the short end! We got to slap hands with every skater. Thanks to my mom:)

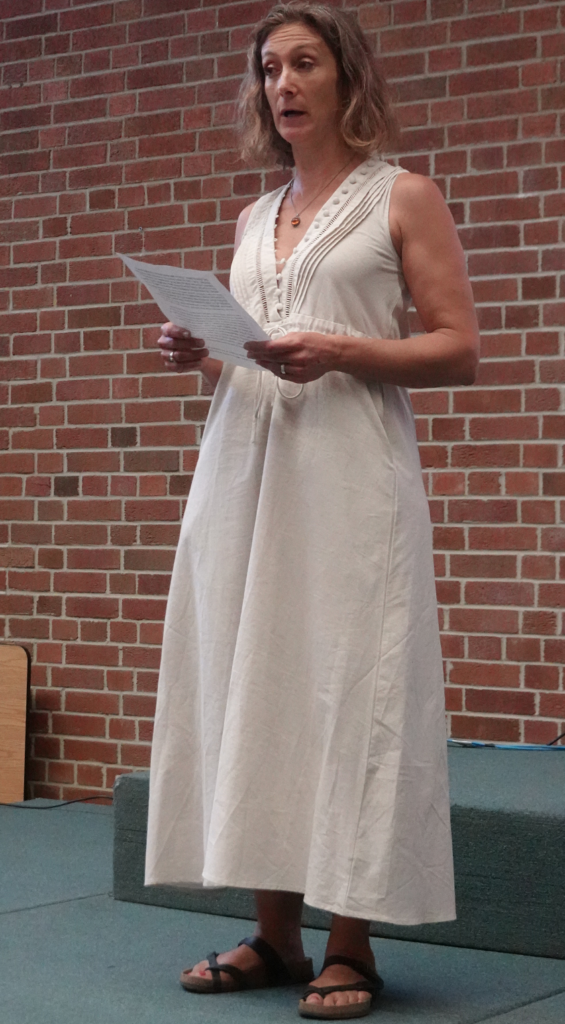

Course Fair – History Courses at YM 2025-26

If you are interested in taking history at York Mills, you have come to the right place. History is a very valuable subject; it’s not about memorizing factoids and dates. It’s about thinking, interpreting, discussing, and inquiring. The skills you gain in senior history courses will help you with any education path you choose because you will always need to THINK!

Grade 10 history (CHC2D), Canada Since 1914, is a mandatory course. It explores events and themes in our country’s history since World World War One. This course is also offered for French Immersion students (CHC2D5).

In grade 11, you can choose between American History (CHA3U) or World History (CHW3M) to the 16th Century. Speak to Mr. Chang about American History.

You can search on this website (Ms. Gluskin’s blog) under the CHW3M tab to see what the course is like. And, read on.

Here are some materials for you to decide if grade 11 World History (ancient civilizations) is for you:

Grade 12 World History starts in 1450, where the grade 11 course finishes. However, grade 11 history is not a prerequisite for grade 12 history.

You can search this website (Ms. G’s blog) under the CHY4U tab to see what this interesting course is like.

Here’s what two of Ms. Gluskin’s former students have to say about taking World History at YM (by the way, one of these wonderful people is a lawyer in and the other was a business consultant and is now working in education administration).

If you would like to ask questions to Ms. Gluskin about World History at YM, she can usually be found in the guidance office.

See you at Course Fair on Wed. February 12, 2025 in room 137.

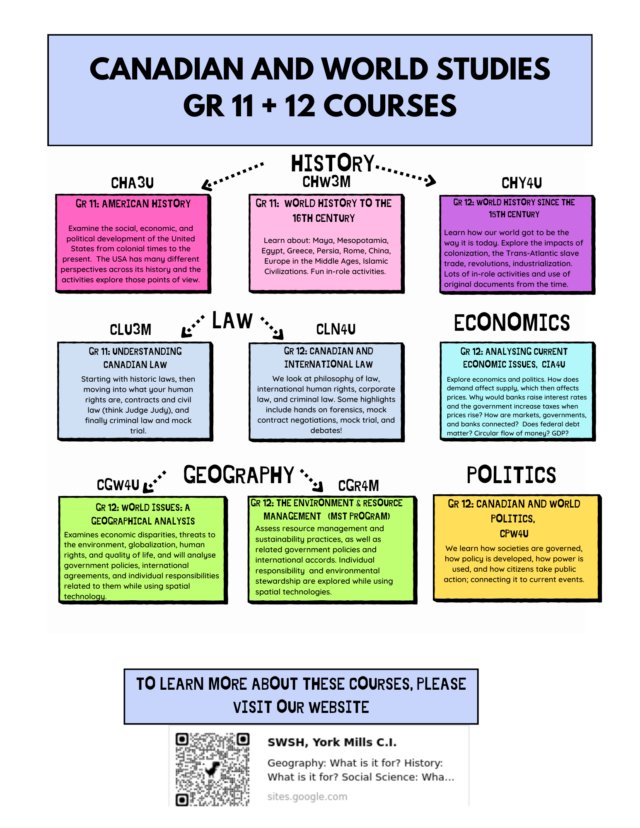

Don’t forget about all of YM’s senior (gr 11 + 12) courses in the Canadian and World Studies area.

Best Books of My Year Off

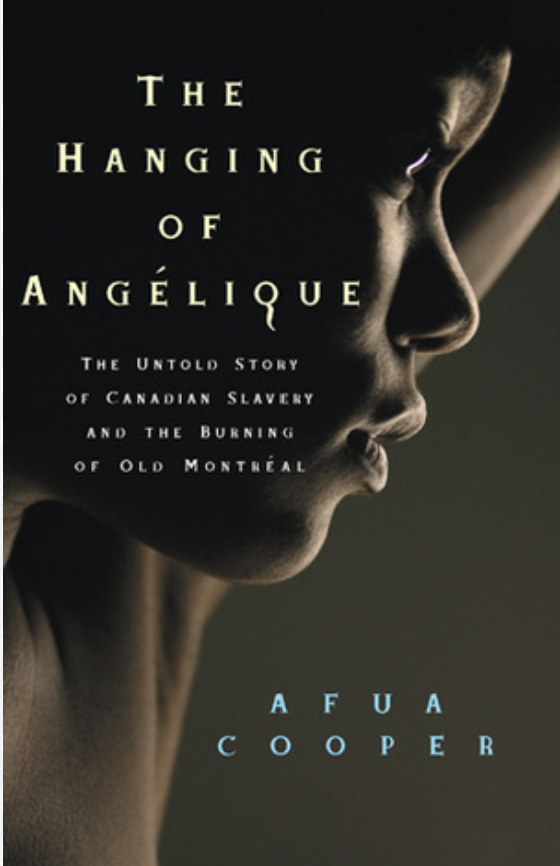

It is difficult to write about The Hanging of Angelique (2006) because it is both so thorough and so sad. Though it is a biography of sorts, it’s an unconventional one in that so little is known about the subject, Marie-Joseph Angelique, a slave in New France in the 1700s. Yes, slavery existed in Canada. Afua Cooper, a very well known and accomplished history professor and poet, takes it on with what one can only call an aggressive (in a good way) approach. She destroys the myth that Canada’s past is slavery-free.

Because Angelique’s life story was not recorded in her own words, Cooper fills in the gaps in Angelique’s life in two ways: she dives into the details of slavery in “Canada” (which of course did not exist as a country at the time) and the slave trade which brought her there from Portugal; she also provides interesting and insightful speculations on how she thinks Angelique might have felt. Along the way, there is a lot of time spent on the “justice” system of New France because Angelique was accused of burning down the house she lived in. In turn, the fire spread and destroyed a chunk of Montreal. She was found guilty, tortured, and killed. Cooper has made excellent use of the court records from the time to show how quick to judgement her accusers were.

Angelique is portrayed by Cooper as a forthright young woman (29 when she was killed) who challenged norms and sought freedom and independence, hence her desire to return to Portugal. Even though Cooper believes Angelique probably did start the fire, she is empathetic about the constraints under which Angelique lived. In a way, she restores Angelique to the full personhood denied her by the legality of slavery in New France.

Just as every Canadian should know about the history of colonization’s effect on Indigenous people, they should also be aware of the realities of colonization and slavery. I for one felt enlightened by the book but depressed that, once again, my history education at university did not live up to the truth. This year in world history class I will make sure that my students understand that slavery and the slave trade were both global and local.

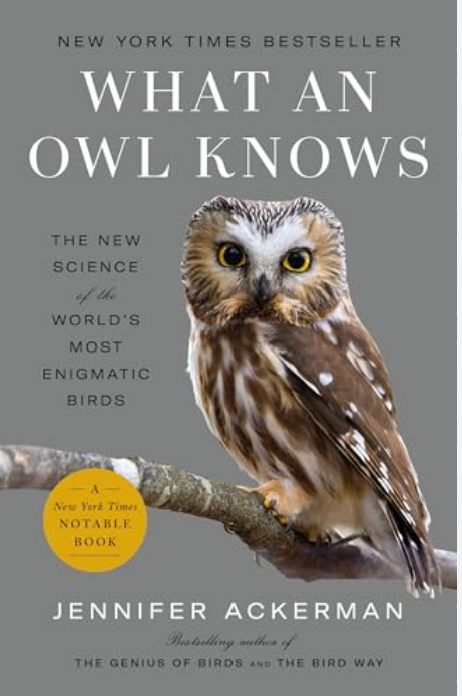

My second ‘best book’ choice is much more in the entertaining and charming vein. In What an Owl Knows Jennifer Ackerman has written a love letter to owls. Ackerman is a well known writer on the topic of birds. Her knowledge is wide. Her respect for her subjects is very strong. Diving deeply into owls, she compares them to other birds, draws on bird research she covered in her previous books, and paints them as absolutely diverse and unique.

Who knew that owl behaviour is so different from species to species? I, being a bird lover but not one familiar with owls, tend – like most people – to generalize owls. Well, no more. There are big owls, small owls, medium owls, tiny owls. There are burrowing owls, owls that nest in snag (a word new to me), owls that roost in the hundreds in trees in Serbia. There are owls that migrate vast distances. There are even some owls that hunt in the day time, not at night. Of course there are a lot of words devoted to owl communication: the toots, hoots, screeches, shrieks, and so on.

I love that she has written so much on the various ingenious ways that owl researchers have devised to study them, whether through netting, observation, or nano-technology tracking (except for the owls that are too small to carry such backpacks). These researchers and volunteers are incredibly devoted to wildlife and endure difficult conditions to improve the science of owls. Ackerman has also visited many rehabilitation facilities where injured owls are both prepped for release into the wild or trained for captive lives as educational ambassadors of their species.

Inevitably, Ackerman must write about the potential fate of owls in the climate crisis in which we live. As for many other animals, it is a sad tale of decline. Yet owls, like others, are showing some signs of adaptation. Let us hope that more and more people, not just birders and ornithologists, take up the call to protect and conserve the owl habitats that shelter these incredible, intelligent and diverse animals.

The Showman

What a book! A biography of a certain time in a person’s life with historical context – how perfect. If Anne Applebaum loved it, I was in (she’s the author of two incredibly detailed and horrifying books on eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Gulag: A History and The Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956).

One should never go in for hero worship, including of people like Zelensky, who are doing pretty big things against very powerful enemies. I knew nothing of his background save for his comedy roots. Simon Shuster taught me that was a tiny drop in a bucket as Zelensky was not just a performer but a writer, director, and producer. He was a very successful businessman whose career was intricately linked with Russia, and who performed and spoke mostly Russian.

According to Shuster’s portrayal, built upon numerous interviews with the president and his colleagues, Zelensky was used to getting what he wanted in the entertainment/business world. Once he won the presidency (on not much of a platform other than to eradicate notorious corruption in Ukraine) with no political record to go on other than his show, Servant of the People, Zelensky was up against not only Vladimir Putin but also the west’s initial intransigence upon Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Big challenge even without the invasion. But then he used his background to become the face of the war and, ultimately, of Ukraine’s survival.

In his transformation from the entertainment industry to politics, Zelensky mastered social media as a political tool, as much for his own people as for the world. Through his direct appeals, he won many over to Ukraine’s cause. He also made it possible for everyone to see the war in real time. It is easy to forget from our cushy position in the west how strong and ugly a force Russian imperialism (and propaganda) continues to be. The author is perfectly placed to capture all of this.

Simon Shuster is a Time Magazine senior correspondent with an obvious focus on Russia and Ukraine. He was born in the former Soviet Union and moved to the US when he was young. He grew up speaking Russian and his mom was Ukrainian. He has relatives who have been directly affected by the war. Banned from Russia in 2015, Shuster recognizes that he doesn’t have direct access to report from there. However, he is a good researcher and a good interviewer, speaking to Zelensky’s colleagues and wife Olena Zelenska numerous times.

Most importantly, Shuster is not an apologist for Zelensky. He doesn’t turn him into a perfect leader.

A must read, as they say!

No Biographies, Eh?

I always write that I don’t normally read biographies (and autobiographies). It turns out I do! So far this year I have read four. Not sure why??? Maybe they’re less intense to read on the subway than my usual historical fare. Maybe I just like complaining that they are not contextual enough.

I can learn something from almost any book, so let’s get on with it.

My friend Julie lent me two books about strong women who, until recently, haven’t received their due appreciation and coverage. The first was Empress of the Nile: The Daredevil Archaeologist Who Saved Egypt’s Ancient Temples from Destruction by Lynne Olson. Even though Egyptian history is my favourite topic in grade 11 World History class, I didn’t know about Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, who was a French Egyptologist. Perhaps I should have because I am familiar with the famous story of the herculean effort to move the Abu Simbel Temples in the Nubian region of Sudan to avoid flooding from the opening of the Aswan High Dam. Little did I know that she was the major force behind this action conducted under the auspices of UNESCO.

Despite growing up in a time when women’s academic pursuits and work ambitions were not generally encouraged or approved, young Christiane Desroches pursued her passions by studying at the Louvre, working on site on archaeological digs in Egypt, and eventually teaching Egyptology. She was both smart and strong in order to stand up to the men in charge who were unused to someone else getting their own way! France had a deep relationship with Egyptian archaeology going back to Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign there. To admit a woman to the ranks was a real challenge to the conservatives at the museum and French Institute of Oriental Archaeology in Cairo.

One aspect of the book I enjoyed was her appreciation of the excavation at Deir el-Medina, the workers’ village outside the Valley of the Kings (where pharaohs were buried in some dynasties of the New Kingdom). She valued objects of everyday life, as she appeared to value the modern day workers who toiled under difficult conditions to the benefit of European archaeological expeditions. Because she wasn’t allowed to officially be part of some of the expeditions, she often served as nurse, tending to ordinary people and getting to know them relatively well.

One interesting non-Egypt related part of her story is her resistance work during World War Two. That’s something I’d like to explore further as it’s a subject with which I am not very familiar. A group of Louvre officials was very involved in moving the museum’s treasures as the Nazis gained control. She risked her life to make sure historically significant objects were protected. This reminds me of the scene in the horrible Netflix adaptation of “All the Light We Cannot See.” The real-life version is much better!

It turns out that moving Egyptian temples is much like moving mountains; it took money (which had to be raised from about 50 countries), clever engineering ideas, and international diplomacy over a period of 20 years. This back story definitely doesn’t normally get as much play as the “move” itself. Told against the backdrop of increasing Egyptian nationalism (in context of hostilities with Britain and France during the 1956 Suez Crisis), it is at least an effort by the biographer to put the subject in context.

One last thing most history teachers (and lovers) should be grateful to Christiane Desroches Noblecourt for is her advancing of famous exhibits such as those devoted to Tutankhamun and Ramses II that toured the world (initially to raise money for the UNESCO campaign). I don’t remember the details, but I know my class went to see the King Tut exhibit in 1979 when it came to the Art Gallery of Ontario. Perhaps it was an early inspiration for my career in teaching world history.

Desert Queen by Janet Wallach tells a similar story of a tough European woman entranced by the “east,” Gertrude Bell, a well-off English woman born in 1868. Growing up, she already displayed the intensity that would mark her whole life’s work. Never one to back down from what she wanted and was disapproved by noble society, Bell attended Oxford and was the first woman to earn a history “first” there, though that did not translate into a degree because no Oxford degrees were granted to women until 1920. While her views were generally considered progressive for the time, Bell was not in favour of women’s suffrage – more for class reasons – see this excellent online exhibit on this fascinating topic. Bell became a travel writer, mountain climber, “explorer” of Arabia, in the imperialist sense, amateur archaeologist, and eventually, a British diplomat in Mesopotamia (soon to become Iraq).

Gertrude Bell wrote enumerable letters home from her various travels and posts, as she had when she was at school in London and Oxford. Therefore, her life is very well documented in the sense that we know what she said about people, events, etc. However, she’s still a difficult woman to truly understand on a personal level. To say she seemed stoic is an understatement, though she did have at least two great loves that did not result in marriage or fulfillment, sadly. Gertrude Bell’s devotion to British imperialism seemed to be the driving force of her life and work. There are times when reading this book I wanted to (excuse the phrase) smack her! Only occasionally did the writer situate her opinions, class privileges and pro-empire positions within the context of the time. I found this incredibly frustrating, and I admit I took it out personally on Gertrude at times. I was sad though, when, in the end, despite her years of service and wide-ranging exploits, she died of a possible suicide, or at least an overdose of sleeping pills, in 1926.

As far as the Middle East goes, if I hadn’t already known how important World War one and its aftermath were to the region and the world, I would have found this book confusing with the often-paradoxical and/or hypocritical French and British promises to the Arabs and Jews, not to mention Kurds, made during and in the aftermath of the war. They all played out in how much control Britain was willing to cede in the newly created mandate of Iraq. Gertrude Bell’s views were initially what one would expect from a hard-core imperialist: keep the British in charge no matter what, and work with the tribes and personalities loyal to Britain, to the point of encouraging the failed King of Syria to become the first King of Iraq – Feisal, son of the Sharif of Mecca. In the end, Bell did soften somewhat to recognize that total British control was not in anyone’s interest, not least Britain’s.

Gertrude Bell’s writings and photographs are today the basis for the Gertrude Bell Archive held at Newcastle University. They have some interesting online exhibits that attempt to take a modern perspective on her imperialist views and how they interacted with her womanhood. It’s a great example for my students of the change in historiography toward uncovering women actors in history who should be part of the curriculum.

Not being a huge Rush fan, some might wonder why I chose to read Geddy Lee’s My Effin’ Life (which, being such a big, well-illustrated hard cover book, is not subway friendly). I can’t really say, but I did enjoy it. He starts off in a very historical way, with the story of his parents, who were Holocaust survivors. He put in the time to research well, and he is certainly aware of the multitude of ways this fact has influenced his life. Probably my favourite aspect of the book is his evolving relationship with his mother. Geddy’s father died young. Expectations were put on Geddy’s shoulders. He did not take the expected path: not excelling in school, taking up rock music, marrying a non-Jew. Meanwhile, Geddy’s mom kept the family afloat by running a neighbourhood store north of Toronto.

He’s also a Toronto boy, so I suppose I liked his references to the various places he lived while growing up, including Willowdale, near where I grew up.

I haven’t read a so-called rock bio before. Geddy saves his passion for his intricate descriptions of various recording processes and tour set ups. I found those interesting. Where he holds back on the details, perhaps understandably, is regarding his personal relationship with his wife. Being addicted to the touring life, Geddy obviously did not spend a lot of time at home. He knew he was often leaving home at the most crucial moments. Therefore, it’s interesting that at times in the book he seems to cut himself off from examining, in depth, his feelings on this topic. It’s not that he ignores the subject; it just doesn’t get the detailed treatment accorded to, say, the production process for an album.

The book runs the gamut of emotions, obviously from the tragic Holocaust stories, and, of course, the sad death of Neil Peart, to the funny band stories, especially the nicknames that they gave each other. Geddy is very funny and has a wide range of interests that he has clearly invested a lot of time into (and some he no longer values – which is good!). In honour of Geddy’s foray into being family historian, I tried listening to some Rush songs that don’t receive as much (if any) radio play; they still aren’t to my taste.

The last thing I’ll say about the book is that it is highlights Geddy’s intense collecting habit. There are many, many photos and documents and odd things throughout the book. As a historian, I admire that. As a person who has a basement filled with stuff, I pity it.

As a figure skating fan, I found it very difficult – yet mesmerizing – to read this book by American skater Gracie Gold. The title Outofshapeworthlessloser refers to the name she gave herself when in the depths of despair trying to make a comeback (or continuation of her career) after some difficult injuries and highly challenging family circumstances.

Without getting too much into detail on a subject where I could expand at great length (figure skating), let’s review Gracie Gold’s major results… In the first part of her career, she earned some very notable finishes at the world level: fourth at the 2014 Sochi Olympics, Bronze medal in the team event (first ever) at the Sochi Olympics, two US championships, fourth at the 2015 and 2016 World Championships. At the time, I didn’t have any particular attachment to Gracie Gold other than admiring her athletic jumps. She seemed very talented but somewhat unable to put together two good programs in one competition, something relatively common in skating.

Appearances can be deceiving, as we all know. As Gracie tells it in her very extremely forthright book, Gracie Gold was a concocted image: the blond hair to match her name, the stylish costumes, the product promotions, the perfect family, and on and on. Underneath it, Gracie endured the harshness of living in the bubble of a judged sport. She relates the soul-crushing styles of two of her coaches, one of them nicknamed Cruella, and the other whose real name she uses. He grew up a product of the Soviet skating system and transported the harsh coaching style to the US. Gracie and her, shall we say, big personality, endured years of what sounds like depravity under his tutelage, until she had had enough.

Due to many intersecting factors, including years of being in a judged sport, injuries and her family falling apart (dad was an anesthesiologist who got caught for using drugs and mom was an alcoholic who had very high expectations of her) Gracie fell into depression and an eating disorder. She suffered in silence for a long time (and highly criticizes adults for not recognizing this) before some kind people in the sport got her into in-patient therapy. That part of her story is pretty well known now.

Some things I didn’t know include that she had a breast reduction, went into coaching, and professes to still love the sport.

Where the book is the most challenging is the frank chapter on her relationship with former skater John Coughlin. As she got very close with him, he helped her career by introducing her to the world of skating workshops. He was being investigated by US Safe Sport for sexual assault when he committed suicide. Gracie plainly states she is of two minds when it comes to the man she considered to be a soulmate; she loved him, he might have raped others. It is really this chapter that got me thinking about the state of skating the most. It is most definitely not the perfect world. No sport is. But for the young, I worry about the effects of pressures and predators.

Gracie Gold has been widely praised for telling her story in a no-holds barred manner. I fully agree and feel every young female athlete, no matter their sport, should read it.

Next up, I’ll be writing about a very profound book of Canadian history (or rather, the story of Canadian slavery usually omitted from Canadian history): The Hanging of Angelique by Afua Cooper. And I am almost finished The Showman (about Volodymyr Zelensky) by Simon Shuster and will surely have a lot to say on it.